When I got to the bed room, I started questioning myself: Did I ever have a vocation to become a priest?; what is a vocation any way?, I just did not have honest answers to these questions, and worst than anything, if being a good student did not qualify me, and being happy in the school was not enough, if having kept an impeccable record of good conduct did not suffice?, what, for heaven’s sake was enough? I just did not have an argument to debate father Gonzalez with, so my not returning to the school was something I had to accept as an order from above which I had no recourse against.

All I knew was that my life was going to change dramatically. My family just did not have the financial means to send me to a comparable school, and most likely I was going to have to settle for a public school of sorts. Public schools were then, as they are now, the place where parents sent their children for education when they have no alternative. Nowadays is even worse in Ecuador, because a radically communist teachers’ union controls public education and refuses to accept any level of performance evaluations from the government or from the parents. No government over the last fifty years has been able to take away the control of the education from this militant union. Any attempt from at least the last ten governments to disrupt the teachers’ unions control of education has failed; the result has been a deeper and deeper hole in the quality of education of young Ecuadorians.

But the question that most tormented me was how on earth was I going to convey the Rector’s message to my parents? Would they understand? Would they be mad at me? Would they keep me responsible for not making it possible for them to have their dream of having a priest in the family come true? The whole 12 hour train ride to Guayaquil, which used to be the best part of the school year, was going to be full of these tormenting series of thoughts.

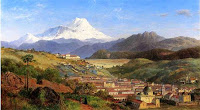

Riobamba, 9000 ft high near the Chimborazo, one of the tallest mountains in The Andes

I went to bed that night with a series of contradicting feelings. Yes, I was going on vacations, but no, I will not return to this school where I have lived for over a year and a half and have enjoyed the happiest years of my life as a student. I packed my clothes in my wooden suitcase for my trip to Guayaquil where my mother and father would be waiting for me at the end of the day, the day after. A child after all, I went to sleep at about nine in the evening and was awakened at five in the morning to get ready to take the seven o’ clock train to Guayaquil the morning after. After good wishes and farewells from the other children a taxi took me and other four children to the train station. The weather was colder and more windy than usual, and by six thirty, in our way to the train station, we could see that many children on holidays had already started to fly their kites in the mostly dusty, desolated and windy streets of this small city.

The train leaving Riobamba

The train took off at the scheduled time and off we went up the mountains to about almost twelve thousand feet were temperatures dropped to between the forties and fifties inside the train, before reaching the breaking point and starting to descend to sea level through some of the most rouged mountains of the Ecuadorian Andes.

As the train slowly ascended through the mountains, my thoughts were in some other place; I couldn’t help but think about what was going to happen after I arrive. I could only see through the train’s windows, the telegraph wire poles going fast backwards as the train picked up speed. Once in a while I could see, and appreciate the view of the green, cultivated almost to their top, mountains as we were climbing them in our way to the coastal plains were the city of my destination was, Guayaquil.

A masterpiece of Sierra country railroad engineering, this railroad was designed and built by the "The Guayaquil and Quito Railway Company", an American - British consortium using the most advanced railroad construction techniques available at the beginning of the twentieth century. Most of the hard labor workers were African Jamaican who had been hired at the end of the nineteenth century and remained in the country until the railroad reached Riobamba in 1905 and Quito in 1912. Many of those workers never returned home as they died from tuberculosis, malaria, yellow fever and other tropical diseases endemic to the Ecuadorian tropics, while working in the construction of this mammoth snaking iron way to the Andes.

But the railroad was completed and for the first time ever, one could travel in only about ten hours from Riobamba to Guayaquil (from the high mountains to the sea level tropics), a trip that at the end of the nineteenth century used to take about a week of horseback riding and lots of endurance to complete it. When completed, this railroad was considered a marvel of engineering which dramatically helped reduce the tremendous gap of mutual knowledge and distrust between Ecuadorians living the mountains (the Serrano, or mountain people) and those living in the Coastal plains (costenos). This railroad, no doubt, was a gigantic advance in the integration of the country. Most of the credit for the completion of this railroad should go to President Alfaro who was tragically assassinated in Quito in 1912. He is now considered the greatest Ecuadorian of all times.

My feelings of fear, anxiety, despair, loneliness and helplessness during my railroad trip could only be compared to the insurmountable odds and mental anguish that some of those unfortunate African Jamaican men must have felt while working for a miserable salary in the construction of this railway, when they saw their fellow workers succumb to incurable diseases caused by the alien environment and subhuman conditions they were working in. The families of hundreds of them never saw or heard from them again, I didn’t know what was going to be my destiny heretofore, I only knew this was going to be a turning point in my life.

In my next posting: WHY WAS I SO MUCH AFRAID OF MEETING MY PARENTS

Tio, your story is amazing. I am anxiously waiting for the next part. It's like a novela....I can't wait to see what happens next!

ReplyDeleteWonderfully written. It is truly an unbelievable story, but all the more memorable because it is, indeed, true. As for a vocation, we all have one. And i truly believe yours was one Father Gonzalez himself would be proud of, which is to be an amazing father, and an extremely generous, giving person to whomever needs a helping hand, whether it be your own children, the children of Ecuador in need of a better education, or a member of your extended family. And that will forever be your legacy. It's funny how everything turns out exactly the way it's supposed to be, right?

ReplyDeleteDear Uncle Rafael,

ReplyDeleteThank you for sharing.... As you continue to tell your story, we will continue to praise the Lord....

Warda