The Cerro Santana (the site where in 1537 the city of Guayaquil was founded by the Spanish Captain Francisco de Orellana) could be seen with all its charm from the boat ferrying the train passengers coming from Riobamba

The lights of the city with all their splendor could also be seen from the boat , ever clearer as we approached the other side of the river in our East to South West short water journey. During the twenty minute ride to get across the river, a couple of the vessel’s stevedores sitting on the floor of the lower deck of the boat, and oblivious to the crowd around them, decided to have their own show and began to sing old songs which they said they used to hear on Radio Zenith, over twenty five years ago in (in the 30's). They did it in a nostalgic way, “those were the sounds of our dearest old Guayaquil” one of them said, and the other answered, “yes, those were the old good times which will never come back”. “Guayaquil is just not the romantic and quiet city we used to know any more”, said the first one, the other nodded approvingly

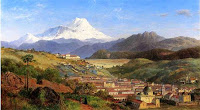

This is how Guayaquil looked in the mid 50's

As the boat docked in Guayaquil, my parents were waiting for me at pier number 5. They were very effusive, very loving, very tender and very welcoming. My father helped me with my luggage and the pineapples, while my mother continued to hug and kiss me as we entered the taxi which would take us to my final destination, Letty’s House in downtown Guayaquil.

At home, dinner fixed by Letty, who was a great cook, was waiting, I could smell the dear and much missed smell of home food, the familiar smell of cooked beans and rice, the fried bananas, and, of course, the dearest smell of my mom´s made bread. Once we all sat around the table, and had thank god for the food we were about to eat, in a ceremonious way dad said, “Let´s all pray and give thanks to our Lord for our son´s return from school after a long time away from us, and for the destiny HE has chosen for him.” After prayer he added, “Let’s eat, since our little priest must be hungry, aren’t you my little son?” His words, which for sure my father really meant, sounded kind of sarcastic to me, especially “our little priest”.

After over fourteen hours without food, I was so hungry I could have eaten a barbequed elephant by myself. “Yes dad, I’m hungry and very tired,” I said in a trembling voice. “I just feel like eating and going to bed right after.” In a way, I was hoping for some kind of a miracle that would get me off the hook. My fear must have been obvious, so obvious that my mother, whom I always though, and still think, could read my mind, soon came to my rescue after I fast ate the main course. She played awhile with her hands over my head and took me off the dining room an into the wash room where I brushed my teeth and then went to bed. I pretended to be very sleepy and asked mom for her blessing before I got in bed. As usual, she made the Holy Cross’ signal with her hands touching my forehead and said, “God bless you always my dear little son, and have a good sleep.” This was the night I was first introduced to the notion of insomnia. Oh Lord, I just wished I could board a flying train and go far, far away, where I could hide my shame from mom and dad, so I would not have to see them face to face and tell them the bad news. It must have been at least three AM when I finally fell asleep and even then, I have nightmares which woke me up at least three times..

At about seven thirty in the morning, mom came to my bed and sat near me, she woke me up with a kiss in my forehead and then she started scrubbing my head as if trying to put order in my always indomitable hair. She repeatedly kissed me all over my head and face, then, she embraced me, made me sit down and said, “Tell me my dearest son, what is happening to you? I know there must be something seriously wrong which you didn’t want to tell us last night, but here I am to listen, and you are going to tell me. Whatever it is, I need to know it, so please, trust me and tell me, I love you much, you can be sure of that”

While she was talking, I felt a mix of despair and hope. She seemed so loving and caring while sitting next to me, yet I knew she was not soft when dealing with her children´s misdoings. Finally, feeling that I had no way out and had to say what I feared to say, I brought up some strength deep from within and said while sobbing, “Mom, I don’t deserve your love any more. I’ve failed you, I’m no good for the family, I’m sorry but that’s how I feel”. She took a couple of minutes before reacting to my words and then she asked: “why are you saying that son?, why are you so severe with yourself?, you have to tell me what happens inside of you, why so much anxiety”. Still sobbing and talking with half words I was able to articulate “I’ve been told at school that I can’t be a priest, that I wouldn’t make a good priest that I can’t go back to school next October”. I stopped for a moment and then said “Mom, I thought I could be a priest, a real good one, but now I can’t return to the Seminar”, and then added with tears in my eyes, “I’m done mom, I’m finished, the dream of having a priest in the family is now over and I have no one to blame but myself, I swear I would have liked to be a priest to make you happy, mom” and continued, “mom, there is nothing I would rationally do to make you unhappy. You know that, don’t you?”, she was listening very carefully but her eyes began to shine like she was about to shed some tears too. Throughout this entire dialog, my mom was calm, amazingly, unbelievably calm, and almost absurdly calm for what I have been expecting. I couldn’t understand it, but, deep in my heart I knew a door leading to hope was slightly being opened. “Oh God, there seems to be a way out of this without farther suffering”, I thought.

After several minutes of silent hugging, kissing, sobbing and crying, my mom resumed our dialog and said, “No, my son, I didn’t want you to be a priest to make ME happy, I have always wanted you to be happy” and added “It would have made me very unhappy had you become a bad priest”, and then continued, “calm down my dear son, it’s OK, I understand; let’s get ourselves prepared to talk to your dad and hope he too, somehow will understand all this. It’s a good thing we are now two to do the talking”. By the way, she said, “how did you do academically? I’m sure you did well, didn’t you? “Yes”, I said, and digging into my old wooden luggage case, I showed her my academic awards. She showed a broad smile, a beautiful smile, a smile comparable to no one’s since her.

Dad wasn’t home that morning, which made things easier for me, and I believe also for my mom. Dad was a man to be feared, a man sometimes I hated to love, but I had now my mom in my side, I felt no longer alone, I felt somewhat relieved.

In my next chapter: FACING JUDGEMENT