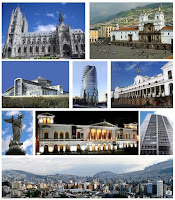

THE IMPRESSIVE COFIEC BUILDING IN QUITO

MY OFFICE WAS IN THE 11TH FLOOR

Dr. Correa was extremely happy to know I could start soon in his bank. He had no objection whatsoever to the fact that that I would still be holding the position of legal representative of Northwest in Ecuador until such day when all legal papers had been filed and sealed and the company had been legally dissolved. We set October 15, 1978, as the day I would start with COFIEC, however, before I officially took office, Dr. Correa wanted me to do a survey mainly in Guayaquil and Quito, regarding the availability of funding from nontraditional local sources of financing, basically knowing the regular banks had been happily absorbing (paying relatively low rates) the savings deriving from a booming economy in the country. I took off doing the study immediately and a month and a half later, on December 1, 1978, I delivered a hard copy of my study to Dr. Correa. I concluded in my study that the country was going through a period of very high consumer confidence, that there were a great number of sources from which our bank could absorb the savings of people and business entities whose banks were not paying them a competitive rate for their money. More than that, people were willing to start saving at pre-determined mid and long-term maturities, provided that the bank would give them a credible document to assure their savings and returns were paid back on time and as requested.

Correa loved my study, he sent it to his lawyers and asked them to think about the “document” through which we could implement my conclusions. The lawyers liked the idea too, and soon thereafter the bank requested and obtained the approval from the Superintendency of Banks for the issuing of the so called “Financial Certificates” through which COFIEC, which as an Industrial Bank was not allowed to take regular savings from the public, would fund itself, entering a market that otherwise it was not allowed to operate in. The Financial Certificates were an absolute success. In the first quarter after they hit the market, COFIEC funded itself so much that Dr. Correa decided to slow down the promotion of this paper. The secret to such a success was the “commitment to buy back” the certificate upon demand from the owner, at any time after the first 90 days after its issuance, giving it, in fact, an otherwise inexistent condition of almost immediate liquidity to the certificate. COFIEC was so well funded at still very good rates that its clients, large industrial corporations, immediately began to benefit from COFIEC loans at better than expected credit rates.

On January 20, 1979, I suffered a very serious car accident in Bogota, Colombia, as my friend Alejandro Gonzalez wrecked his car (in which I was a passenger) against a wall, late at night while he was intoxicated. I needed to go through a very serious “face repairing” operation which, in a matter of six weeks which included important post operation care, put me back in the world. This delayed by two months my taking office at COFIEC.

THE CARDINAL SPELLMAN SCHOOL IN QUITO WHERE MARIUXI ATTENDED HER KINDERGARTEN YEAR

Finally, I took office in COFIEC (literally a big corner office in the 11th floor of the most modern building in Quito) on February 15, 1979. I was the bank’s VP-Finance and had direct access to the CEO’s of all the banks in the country with which our bank was doing business (the 10 largest in the country). I enjoyed a great amount of confidence from our bank’s CEO himself, and the respect and friendship from most of the staff of our bank, as well as the envy, I suspect, from a few old time officers of the bank, who felt jealous due to my sudden (almost abrupt) rise in the ranks of the bank. I enjoyed my work at COFIEC, just as much as I enjoyed it at Arthur Andersen and Northwest. I adjusted just fine and quickly to my new responsibilities, which included business and personal contacts with the CEO’s and top finance officers of many of the largest companies in the country in Guayaquil and Quito. At this point I used to think of myself as having reached heights that I would have never imagined. Here, I used to think, it is the same humble little boy who used to carry morning bread from a bakery to the grocery stores in a tricycle only 20 years ago!. Who would have thought in those early days that I would be able to take on such tremendous responsibilities in one of the largest and most prestigious banks in the country?. I suspect not even my mother, who always thought that with effort and hard studying, anything was possible. I wished then, as I wish now, that she would be alive to see me, achieving what I had achieved while remaining basically the same humble man I had always been.

MARIUXI ¨GRADUATES¨ FROM KINDERGARTEN

AT THE CARDINAL SPELLMAN SCHOOL IN QUITO

Meanwhile, the Northwest branch’s dissolution was going much slower than expected, the Ecuadorian official entities are not known today for the efficiency with which they mind their business, but back then it was absolutely incredibly how slow they were and how little they cared for efficiently fulfilling their duties. By the end of 1979, a year after the start of the dissolution process, there were still several things that needed to be taken care of, before we could safely say we were done with it, so I called Glen Nelle in Houston and told him I was disappointed with the pace at which we were going and suggested that he found a replacement for me, to see if the process would speed up. At this point it had been already more than a year that I had been drawing two salaries: one from COFIEC and one from Northwest. Glen was emphatically against the idea and said that I should not be worried about the time the dissolution process was taken.

At this time, Glen went even farther and said that he had been thinking of me in connection with some other international projects once I was done with Northwest in Quito. Specifically, he wanted me to think about moving to the US in the somewhat near future as he thought he might need me in connection with the company’s international business, particularly with those in Argentina.

CARDINAL SPELLMAN´S GIRLS, 30 YEARS

AFTER MARIUXI ATTENDED THIS SCHOOL

I discussed this with Fanny, as a family we were at a peak of a wave of wellbeing, we were enjoying an incredibly good social, economic and family life, I was making twice as much income as any comparable executive of my level in the whole country, our children were growing healthy and happy and were attending the finest private schools in the country. So, thinking of a change was a subject that needed to be given a lot of thought, we needed to compare what we had, which was as good as could be, with something we might have if things went fine. Fanny did not speak English, the kids were very young, and to make things a bit more wondering, Fanny was pregnant for the third time. So, my wife and I had a lot of material to work with before we made a decision on this new challenging proposal.

SALT LAKE CITY, OUR NEW DESTINY IN 1980

We decided that I needed to talk to Glen Nelle again, so as to find out some more specifics about his idea, and I also called and talked to Piero Ruffinengo (a young lawyer I had worked with while doing the economics of the gas project, who has been closely associated with the Ecuadorian project), in Salt Lake City. Glen thought that I could be transferred to Houston, were his office was located, while Piero thought that Salt Lake City would be a better place for my family, at least for some time, while the family adjusted to the US way of live. Talking about the subject went back and forth for a few months until April 1980, when the Northwest dissolution was finally over, and a decision was taken to locate me in Salt Lake City, that I needed to be in Salt lake by July 1980 and that, I would be assigned the possition of Finance Manager of Northwest Argentina, the Northwest Affiliate doing business in that country, mainly through another affiliate, APCO Argentina, which co owned a very productive oil field in the province of Neuquen, in the Argentine Patagonia. The other partner in this venture was Perez Companc, a large Argentine conglomerate.

In my next Posting: SALT LAKE CITY